Introduction: The Agenda of Innovation in the West Bank

Palestine represents a unique geographical setting for innovation to flourish. Occupied by Israel since 1948, it currently represents ‘the last occupied country in the globe to date where entrepreneurs are required to operate in extremely challenging situations’ (Baidoun et al., 2018). A range of economic and social challenges persist in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (oPt). Nearly five million Palestinians (PCBS, 2019) are spread across the disconnected and fragmented geography that constitutes the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and all movement within the West Bank, as well as that between the West Bank and Gaza and abroad, is fully controlled by the Israeli government, meaning that it is restricted by checkpoints, a complex system of permits, identification cards, separation walls, etc. (Boulus-Rødje et al., 2015).

The economy of oPt faces the monolithic challenge of being made largely dependent on Israel for trade and economic opportunities. The local Palestinian economy has witnessed a steep decline in growth in recent years due to the occupation’s economic and social restrictions, which has hampered its ability to create jobs and raise living standards. The unemployment rate in the oPt has remained stubbornly high, reaching 30.8 per cent (World Bank, 2019).

Technological entrepreneurship and innovation is currently perceived as an engine for economic growth worldwide, specifically in developing societies (Aldairany and Quoquab, 2018). Indeed, the global startup economy continues to grow at an unprecedented speed, and it is thought to have a value of $2.8 trillion (Startup Genome, 2019). Research has shown that a country’s economic development prospects strongly correlate with the diversity of its available technological bases, which has frequently prevented resource-based economies from advancing (Hidalgo et al. 2007). This has called the need for attention to how these issues are entangled in a transnational economy driven by 21st-century global innovation and start-up ecosystems (Fraiberg, 2010). In this article, I extend this line of work through a case study within an emerging high-tech innovation ecosystem in the oPt.

Driven by the promise of technological innovation as a solution to the economic and social inequities of the Israeli occupation, tech entrepreneurship has been taking ground in Palestine. Innovation is considered a sector capable of flourishing under the occupation, as it is unhampered by the material realities of the occupation, such as checkpoints, soldiers, and separation walls. Core to these efforts is the development of an innovation ecosystem comprising a growing list of venture capitalists, incubators, accelerators, co-working spaces, and meetups (Fraiberg, 2020).

Palestine’s Innovation Ecosystem & Rawabi Tech Hub

The high-tech ecosystem in the oPt is a complex, deeply distributed, emergent network of venture capital firms, incubators, accelerators, meet-ups, and start-ups. To estimate the size and scope, the World Bank assessed that the ecosystem comprised approximately 241 active start-ups (Mulas et al., 2018) and includes a recently established Tech Hub. Located in the rolling hills of the West Bank, 17 kilometers from Ramallah, the Rawabi Tech Hub (RTH) is part of the city of Rawabi (“hills” in Arabic). With construction beginning in 2010, the city of Rawabi is conceived as Palestine’s first ‘smart city’, complete with optical fibers, solar panels, electric vehicles, green areas and the adequate infrastructure for a tech-oriented center in Palestine. The city is a mammoth $1.4 billion project that was largely privately funded by real estate investor and entrepreneur Bashar Masri in partnership with the government of Qatar (Beit Magazine, 2019).

The RTH aims to turn Palestine into a regional hub for high-tech multinational businesses, and is part of a deliberate effort to establish a cluster or ecosystem of innovation (Lieber, 2018). Masri and his team envisions the tech hub evolving into an epicenter of Palestinian high-tech, a small, concentrated cluster that will slowly develop into a bustling technological environment, thus serving as the nucleus of a future Palestinian state’s own Silicon Valley.

The implementation of the RTH, as an innovation initiative, has become a unitary dominant vision for Palestine’s innovation future. It reflects a socio-technical imaginary aimed at orienting the country’s innovation institutions, actors and resources towards those pre-established goals and to employ strategies so that this particular pathway of innovation development could evolve. The tech hub reflects the perspectives of actors who possess and exercise power in Palestine’s innovation future and reveals whose voices are able to mobilise sufficient resources to support their favored strategies and ways forward. The Tech Hub, thus, institutionalises the voices of these key actors, and simultaneously marginalises the alternatives.

This paper brings to fore the key characteristics of these visions or ‘imaginaries,’ and describes the tensions and contestations surrounding them, their production, and their extension. How do various actors envision Palestine’s innovation future through the RTH? What unique social, political and cultural determinants underwrite these imaginaries? This paper focuses on knowing the ways in which varying imaginaries are framed and, vice versa, the ways in which these imaginaries are used to justify the processes of world-making.

I argue that RTH, as an innovation initiative, takes on several contesting imaginaries on Palestine’s innovation future, resulting in tensions and frictions that seek to impact the sustainability of Palestine’s innovation ecosystem. This recognition of heterogeneity in framings provides a dynamic perspective on how different social groups can articulate competing imaginaries within a specified political space and draws attention to the strategic use and implications of representations of future imaginaries that guide technological and economic activities. This, in turn, could serve as a precondition for more inclusive and sustainable ways of envisaging and framing innovation futures.

Sociotechnical Imaginaries as a Conceptual Lens

Ideas about what the future can be serve as powerful triggers of action in the present since these visions are embedded into decisions affecting the sociotechnical fabric of society. As framed in this paper, ‘sociotechnical imaginaries’ connects creativity and innovation, and even more technology, with the production of power and social order to attain “desirable futures" (Jasanoff, 2015). To be considered socio-technical imaginaries, these visions of desirable futures are “collectively held, institutionally stabilised, and publicly performed” and “animated by shared understandings of forms of social life and social order attainable through, and supportive of, advances in science and technology” (Jasanoff, 2015). Sociotechnical imaginaries are thus temporally situated and culturally particular and are both products of and instruments of the coproduction of science, technology, and society (Jasanoff, 2015).

While they describe desirable futures, imaginaries also delimit alternative ones. Therefore, while there may be a dominant national sociotechnical imaginary, there are other imaginaries that compete to be materialised (Jasanoff, 2015). Imaginaries can gain traction and be strengthened through actions of power, reiteration, and ongoing coalition building (Jasanoff, 2015). In other words, there are a variety of ways by which they can be performed. Studying imaginaries entails being attentive towards how they are able to link past and future times and normalise ways of thinking about many possible future worlds (Jasanoff, 2015). Moreover, the power of imaginaries can reveal the contested ways in which sociotechnical and material futures are imagined and strategically deployed. It also presents the various ways these futuresjustify new investments in science and technology, promote certain development pathways, and, even, validate the inclusion or exclusion of certain actors in the decision-making process (Jasanoff, 2015). This paper uses this concept to frame and describe the contesting imaginaries of RTH, as a dominant entity that shapes Palestine’s innovation future.

Central to this study is also the conception of space as comprising heterogeneous streams of activity. Massey refers to these interwoven strands as “throwntogetherness”: forces, positions, ideologies, uncertainties, tensions, complexities, and ambiguities of economic social and political life (2005). The focus on multiple and emergent stories in the oPt is particularly relevant in a region where contested narratives are deeply entangled in the construction of the social and physical landscape.

Methodology

Employing a case study approach, my analysis of the core sociotechnical imaginaries of RTH, how they are being articulated and performed were derived entirely from secondary research, and my data sources involved the gathering and analysis of news articles, official discourses and guidelines, public events, and surveys on the public perception of innovation processes to date. I also carried out a content analysis of official platforms related to RTH, such as the official websites and companies within the ecosystem

These published outputs provided accurate and precise details on the innovation initiative, such as the positioning of the actors involved in the development of the tech hub. They underscore the imaginaries by which their proponents envisaged the world and are, therefore, key tools in materialising their visions of desirable futures. This wide array of data sources enabled sufficient data triangulation to develop credible and compelling narratives and to achieve conceptual validity.

Using the methodological approach of Grounded Theory, content and discourse analysis was conducted on the gathered sources via a systematic line-by-line reading. Descriptive themes were then formed through the categorisation of different texts that conferred the same meaning. Subsequently, analytical themes were formed by re-reading these descriptive themes, to then develop the framing of the three core imaginaries. This was done specifically to identify who the ‘prominent actors or institutions’ are in the production of the imaginaries and their place in RTH, and the means by which the imaginaries are ‘extended or embedded’ in public discourse. The ‘storylines’ that then emerged from these multiple sources are unpacked to provide insights into the ascendancy of some imaginaries and, by contrast, the subordination of the others. Vital, therefore, in the analysis is to find and identify these recurrent discursive elements as statements re-presenting modes of expression and practices.

Analysis: Core Imaginaries of Innovation Futures

Three different core sociotechnical imaginaries emerge on how actors envision Palestine’s desirable innovation future through their various engagements with the RTH. The dominant imaginary speaks to innovation as the foundation for co-existence that ultimately enhances Palestine’s industrial growth as a high-tech futuristic region. The second imaginary constitutes the future of innovation in Palestine to mean interdependency and trust between Israeli companies and Palestinian tech workers in meeting their economic needs. The third imaginary constitutes the fostering of a Palestinian innovation future to mean total sovereignty and autonomy from settler colonial control. I describe them in turn.

Imaginary 1: Future of innovation as building a high-tech region through co-existence

The first imaginary dominates the vision of Palestine’s innovation future through the RTH and occupies prominence in the narrative of how the country’s innovation ecosystem ought to function and proceed. This imaginary is largely manifested in Bashar Masri’s official vision for the Tech Hub, the viewpoints of Israeli companies directly involved in the development of RTH, and the design of the Tech Hub.

The Palestinian employees of Mellanox Technologies, an Israeli tech company, are based out of RTH. Eyal Waldman, Mellanox’s CEO and president, shares how the company began the working partnership with Palestinians, where at first “the Palestinians were afraid to come to Israel. Their only previous contact with Israelis was with soldiers at a checkpoint or in their villages. We told them that nothing would happen to them. Today everyone is satisfied and relations between workers are good – and that’s one of the most important things” (Haartez, 2018).

Similarly, David Slama, senior director at Mellanox Technologies, shares how predisposed ideas about what Israelis and Palestinians think the other can do or cannot do are refuted almost immediately in the innovation space, where “for many of the people on both sides, they are meeting one another for the first time in [a high-tech setting]. So, this is the first opportunity to meet each other and talk about sports and hobbies.” He notes how “it’s a joy to see the Israeli and Palestinian employees working together” in RTH as a space of innovation, where ”even if at first there’s a little wariness on both sides, after a few hours of working together they forget the conflict, and then they’re working together and relationships are better” (Haartez, 2018).

The strong narrative of Israelis and Palestinians overcoming the initial wariness of working together, and the embeddedness of relational terms such as “working together” and “relationships” used by key players within RTH, highlights the imaginary of co-existence via innovation.

RTH’s focus on Israeli-Palestinian Tech initiatives that foster co-existence is portrayed as a critical element in building a flourishing high-tech Palestinian state, where, responding to a question on whether he was happy to have Israeli investors in Rawabi, Masri shares how “any investor that comes to Palestine and creates jobs for the Palestinians is more than welcome,” and hopes “that large multinational tech companies with headquarters in Israel, such as Google or Intel, will open up outsourcing offices in Rawabi. Another hope is that Israeli companies themselves will outsource to their Palestinian neighbors” (Lieber, 2018). As such, Masri envisions Israeli-Palestinian Tech initiatives ultimately bolstering the potentials of RTH to create new job opportunities and business prosperity in the ICT sector,and aiding the visibility of Palestine as a high-tech region.

Advancing the notion of Palestine as a futuristic high-tech region through innovation, the spatial design of Rawabi city and RTH itself aims to meet the conditions of international legitimacy as an innovative high-tech region (Bayati, 2009). The goals for the city design were to draw upon international urban planning principles, and prepared in consultation with architects and engineers, trained in global city models and in technological innovation. Recently Rawabi has also been invited to participate in the Cityquest Forum, validating Rawabi as a place that ‘creates flourishing urban societies’ (Bayati, 2015). Palestinian engineers and software developers from around the West Bank come to work in a well-equipped, brand new urban setting known as the Q Center, an upscale commercial centre with residential housing, office space, shops, restaurants, and entertainment. Within the RTH is CONNECT, its open-space, collaborative, co-working space that is reminiscent of WeWork (Press, 2018). Here, RTH is designed as a place of optimism and potentialities, not only making it a distinct, memorable destination, but to improve networking and communication flows between Israeli and Palestinian colleagues and innovators.

This imaginary of peace building via innovation to bolster Palestine’s industrial growth is further reinforced in the viewpoints of other advocates of Israeli-Palestinian high-tech partnerships. Yadin Kaufmann, co-founder of Sadara Ventures, a venture capital fund that invests in Palestinian tech firms to operate in the Rawabi-based tech ecosystem, cites how innovation initiatives like RTH “build a technology ecosystem that powers Palestinian economic growth, l reduce their reliance on foreign aid, improve the lives of millions of people, and help lay the groundwork for lasting peace” (Kaufmann, 2017).

While this is the dominant and official imaginary of innovation future in the country, there are other ways by which the futures of innovation in Palestine are envisaged. Two of these alternatives have surfaced as imaginaries.

Imaginary 2: Future of innovation to mean interdependency and trust

The first alternative imaginary to the dominant growth-led imaginary previously described is one envisaged and advanced by both Israeli companies and Palestinian tech workers. Their imaginary pictures the type of stakeholder dynamics that ought to drive the region’s innovation ecosystem, envisioning it as one that is fueled by an interdependency that would enable both parties to address their economic needs.

For Israeli companies, a high-tech relationship between the two populations solves the Israeli high-tech industry’s shortage of engineers through the engagement of Palestinian tech workers. Mellanox today employs over 120 Palestinian, who are involved in developing software, hardware and user-interfaces, among other areas. Slama shares how “the Palestinians help us achieve our [hiring] goals. We have the relevant engineers, we have the relevant ideas and unfortunately, here in Israel, we’re missing talent [that the Palestinians have] on their side. Together we can build a bridge that develops great products for the whole world” (Haartez, 2018).

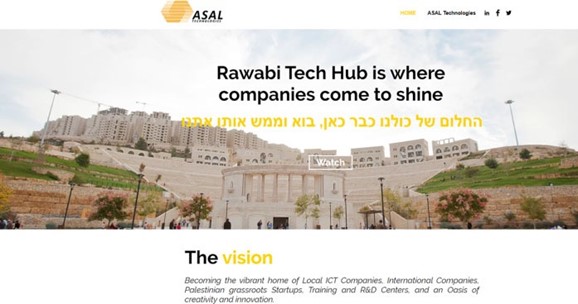

Similarly, ASAL, a software and IT services outsourcing company based in RTH employs some 250 technical experts around the West Bank and the Gaza Strip to cooperate with Israeli companies. Murad Tahboub, CEO of ASAL Technologies, shares how “just one hour’s drive [from Tel Aviv], we have a pool of talented, available engineers. The demand here is much less than the supply. This could be utilised for the Israeli and international markets” (Haartez, 2018).

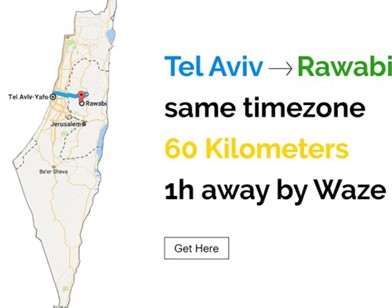

The imaginary of interdependency is articulated in ASAL’s marketing materials, where the ASAL Technologies webpage (see Figure 1) displays a picture of Rawabi City along with the English text “Rawabi Tech Hub is where companies come to shine.” Below this text is a tagline in Hebrew: “The dream for all of us is here, come realise it with us” (Asaltech, 2020). The code switching to Hebrew further signals how the company is aligning with the Israeli high-tech industry through a shared vision for interrelated technology development. The uptake of English indexes a global identity that indicates a shared vision of Israelis and Palestinians working closely together in pursuit of the entrepreneurial dream. Underneath is a map of Israel and the oPt (see Figure 2) that illustrates the distance from Tel Aviv to Rawabi. The colorful text alongside the map, “Tel Aviv->Rawabi, same timezone, 60 Kilometers, 1 h away by Waze” highlights the short distance in space and time between the two neighbors, making the travel, and therefore working partnerships, appear hassle-free (Asaltech, 2020).

Figure 1. RTH as marketed to the Israeli start-up ecosystem on the ASAL webpage (2020).

Figure 2. A Waze Navigation map on the ASAL website (2020).

Indeed, outsourcing through RTH is an attractive option for Israel-based firms because of its proximity, cultural familiarity, and supply of Palestinian engineers. This envisioning of interdependency in Palestine’s innovation ecosystem is thus unwritten by underlying ethos of affordability, reliability, and accessibility on the part of Israeli companies.

On the other hand, RTH serves as a beacon of empowerment for Palestinians while under Israeli occupation, with the promised delivery of economic opportunities via jobs in well- performing Israeli companies, and a vision of prosperity and good life. The present imaginary of economic stagnancy in Palestine’s economy explains why Palestine’s innovation future is seen as part of a process that needs external support from Israeli companies. While surrounding countries such as Egypt or Jordan face unemployment rates that hover at 12-18%, unemployment in the West Bank reaches 27% with more than 42% of those unemployed being young people (20-24 years). Innovation initiatives like RTH appear to solve this problem, trying to attract international investment with benefits such as tax incentives or security (Beit Magazine, 2019).

The outsourcing by Israeli companies, as facilitated by RTH, is expected to not only create jobs for Palestine’s young graduates and entrepreneurs, but also to equip Palestinian engineers with greater experience and knowledge capital through their exposure to Israel’s multibillion dollar start-up ecosystem to be self-sufficient. This imaginary is enacted by the story of Husam Kahalah, who left his job at ASAL about a year ago at the time of writing and moved up one floor to the CONNECT co-working space in RTH. The 33-year-old Palestinian worked for ASAL for five years before moving on to a German car-sharing start-up, where he develops Android and iOS applications for the Berlin-based company. Thanks to “fantastic internet connections” he can work and live wonderfully here. Compared to the German market, he might get paid little, “but what we get here is good for us”. Kahalah has also moved to Rawabi privately, where the father of two lives with his family in a 185 square meter rental apartment that he wants to buy eventually (Sueddeutsche.de, 2019).

The vision of economic self-sufficiency through innovation is thus linked to a wider national narrative of economic stagnancy and the struggle for Palestinian statehood. Through the RTH, innovation in Palestine is thus framed as an overhaul of inherited oppressed identities and empowerment after generations of occupation through ‘a comfortable and dignified existence’ (Rosen, 2013).

Central to this imaginary is the vision of the 21st-century start-up economy.

Circumventing the regime of mobility imposed by the occupation and its tightly controlled borders, the IT sector is not subject to the same restrictions as physical products. With the possibility of “bypassing physical check points, metal detectors, roadblocks, and soldiers,” work opportunities in the IT sector hence offer more promise of developing “semi-economic independence and self-sufficiency” (Bjørn & Boulus-Rødje, 2018).

Innovation in Palestine is envisioned as a mutually beneficial and interdependent symbiotic relationship through Israelis and Palestinians having a stake in each other’s future, shunning political tension ideology in favor of pragmatism. This win-win situation is succinctly described by Tahboub, where “Israelis need workers, and we can supply the demand at an attractive price. That momentum could lead us to establish a genuine Palestinian high-tech industry” (Haartez, 2018).

Imaginary 3: Innovation as Sovereignty and Autonomy

The second alternative imaginary to the dominant national imaginary emerges from a subset of Palestinian society that is represented by several innovation nongovernmental organisations and activists in Palestine on what the trajectory of innovation in Palestine should entail.

The present pursuit of the RTH in fostering Palestinian-Israeli collaborations through innovation is suggested to represent the economic normalisation of settler colonialism, where Palestine is not colonised in the “common sense” of the word, but as a nation in its abstract sense and as a territory more concretely, faces a form of colonial subjugation motivated by emptying the land of its inhabitants rather than “civilising” the people (Kozaczuk, 2015).

Contrary to Masri’s claims to be working for “building Palestine” through the RTH (Lazareva, 2015), groups such as the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement have deemed that his actions have in fact been more in harmony with Israel’s policy of “economic peace” for the West Bank, that is, the sidelining of basic Palestinian rights, including the right to self- determination in favour of economic gains for an elite minority, as part of its carrot and stick approach that rewards obedience to Israeli dictates. The construction of the city of Rawabi in particular has been condemned as the normalising of economic relations with Israel, where Israeli companies were “invited” to bid for contracts (BDS Movement, 2012). It has been argued that Rawabi is a bubble for only a privileged social class willing to trade independence and self-determination for a bourgeois and capitalist lifestyle (Abunimah, 2012).

The imaginary of innovation through autonomy and sovereignty, as enacted by the BDS movement, is focused on “civil, peaceful, morally-consistent accountability measures” that do not “undermine our struggle for our inalienable rights”, thus projecting a strong connection with the ongoing struggle for independence from Israeli occupation (BDS Movement, 2012). Commenting on the development of RTH, Wasel Abu Yousef, a senior official of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, asserts how “all Palestinian factions and nongovernmental institutions, as well as all the Palestinian people, have made a decision to boycott the occupation forces, which is something that should apply to everyone, including Rawabi” (Melhem, 2014). Indeed, this imaginary of building autonomy and sovereignty through resistance is not specific to the innovation sphere - many Palestinians believe that until the Israeli occupation of the West Bank ends and Palestinian state is established, Palestinians must refrain from anything that treats the status quo as normal.

This imaginary of innovation as a tool for Palestinian autonomy and sovereignty is reasserted by Bishara Arees, a Palestinian academic who claims that the first thing needed to revive and elevate the Palestinian high-tech sector is to establish a clear, unified project that serves Palestinian economic interests at a grassroots level. “With individuals, on competencies, schools, and already existing companies, we can build a tech network that includes all private companies and associations… to “offer an alternative, a new proposal and a unified economy” (MIFTAH, 2022). Such an organisational structure in Palestine’s innovation ecosystem can be observed currently in small grassroots organisations like Build Palestine, a youth-led innovation organisation that supports the social innovation sector in Palestine by connecting Palestinian and international funders who are looking to support start-ups across the West Bank and Gaza making an impact within their communities (Buildpalestine, 2022).

The innovation future that nongovernmental organisations, like the BDS movement and Build Palestine, and academics such as Bishara, are trying to instill—one produced out of local needs and local capacity—has started to extend into the larger Palestinian polity locally and in the diaspora. This process of embedding is done through hosting a number of mentorships and workshops with Palestinian entrepreneurs and maintaining an active social media presence (Buildpalestine, 2022).

The imaginary produced in this field can be considered a form of prefigurative activism. These are approaches that focus on the development, implementation, and sustainability of local autonomous innovation solutions where citizens can directly engage in social action, without the participation of Israelis. For this imaginary to be durable, it needs to be continually embedded.

Discussion

This paper reviews three core sociotechnical imaginaries on the future of innovation in Palestine as they compete for dominance. In so doing, this study fills in theoretical and empirical gaps in our understanding of how the futures of innovation could be envisaged and navigated. Theoretically, the paper enriches our understanding of the concept of sociotechnical imaginaries as applied in the nexus of innovation in a country with a conflict setting. Empirically, the paper shows how Palestine’s multiple actors, their interests and politics, continue to shape these imaginaries of innovation. Further understanding these tensions and politics is key in driving coherent and sustainable innovation policy - one that, ideally, has the strongest societal support. The paper gives shape to sociotechnical imaginaries and their potential role in empowering Palestinian publics and shaping a normative direction for their own futures of innovation. This section discusses and concludes the paper by highlighting the key tensions occurring across the three core imaginaries described, as well as some thoughts on ways forward.

As shown, the resultant imaginaries continue to undergo complex and heterogeneous processes, suggesting that there is actually no singular reality. Although Bashar Masri’s vision of RTH is currently the dominant vision of innovation in Palestine, other realities suggest that the production of how Palestine’s innovation future ought to develop is still an ongoing, contested process. Two key observations regarding these contesting imaginaries can be made: (1) imaginaries intertwine with the political economy and (2) that the dominance and/or marginalisation of imaginaries are contingent on issues of power and resources.

Firstly, it appears that Palestine’s contesting sociotechnical imaginaries on innovation are deeply linked to how a political economy ought to operate. Contingent upon the first and second imaginary is the heavy endorsement of a neoliberal logic within innovation, where the Tech hub gains legitimacy as a symbolic achievement towards peace between Palestine and Israel through an innovation economy. It highlights the imperative of RTH as a spatial model of neoliberal peace building, which rest on the ideal that peace can be built by the economic ‘facts on the ground’ and is grounded within a neo-realist belief in the economic interdependency between Israeli companies and Palestinian tech workers (Kozaczuk ,2016). Neoliberal peace building, in essence, is founded in capitalist economic homogenising policies, and core beliefs of liberating economic policies as systems that behold peace at home and abroad (Mann, 1999). The model relies on the state to provide for the ‘human well-being [that] can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterised by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade' (Harvey, 2005). Thus, through the sense of equality and economic opportunity that Masri hopes to foster in RTH, innovation promises the creation of a social and economic existence in the West Bank that is decoupled, as much as possible, from the Middle East’s tense and labyrinthine politics.

I argue that this narrow, normative framing of the relationship between innovation and the neoliberal economy is deeply problematic in how there appears to be a low regard for any political dimension in the depiction of innovation by the first two imaginaries, especially amidst the extremely politicised setting of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This neoliberal discourse of economic peace depoliticises innovation and the truth of Israeli military occupation of the West Bank and relies on technological innovation as a panacea for both Israelis and Palestinians to cope with the political tensions entailed in the Zionist regime.

The third imaginary, comparatively, questions the role of the market by criticising the notion of a Palestinian innovation ecosystem that relies greatly on Israeli economy, in the context of ongoing wars and occupation. This imaginary raises concerns about the neoliberal ethos that prioritises market-led innovation partnerships as a solution to the economic and social inequities of the Israeli occupation and introduces the notion of local sovereignty and empowerment by controlling the processes of innovation from locally distributed systems solely within the oPt. This emergent, but marginalised, imaginary brings to fore how to build local innovation capacities, particularly at the grassroots level.

Secondly, the ways by which actors and institutions who deploy their imaginaries in an attempt to shape Palestine’s innovation futures are contingent on their power and resources. Power structures that exist in the “tangible” realm do not disappear in the “virtual” realm, and the consolidation of power and resources has direct implication in terms of the ability of actors and institutions to persuade people that their imaginaries represent the most durable way forward for Palestine’s innovation future. In the first imaginary, the RTH as a built environment, plays an integral role in the consolidation of power by Israeli firms and Palestinian elites who have vast access to resources, and hence, have the ability and capacity to circulate this vision of the future far and wide. The second and third imaginary, by contrast, are embedded using more distributed resources. This dearth of political rights, power, and resources would reduce the capacity of these contesting visions of desired future of innovation to be extended.

Indeed, the expectations of autonomy and self-sufficiency that Palestinian tech workers hope for in relation to the outsourcing sector do not appear to be fully met. It has been argued that Palestinians continue to be exploited with lower wages, even in the virtual realm, and developers do not acquire sufficient multidisciplinary knowledge and experience to spark a generation of independent startups, as the tasks that were being outsourced are mostly non- innovative and repetitive, entailing a narrow focus and fewer opportunities to acquire multidisciplinary knowledge. After all, the outsourcing sector typically focuses on servicing, not on innovating (Nina & Bjorn, 2021). As such, the economy thus remains insufficient to realise economic sovereignty due to the persisting political uncertainty and “the structural imbalance between a low-cost Palestinian economy and high value Israeli economy, and…individual self-interest trumping national solidarity among Palestinian firms” (Burton, 2016).

Ultimately, those with more resources at their disposal are likely to register the most successes in terms of producing the dominant imaginary of Palestine’s innovation future. Thus, the question of who is allowed to shape Palestine’s innovation future is an important one that needs to be further reflected on.

Conclusion

This paper, in conclusion, points to a messy, complex, and heterogeneous reality of innovation that is continually navigated and negotiated in their contestations. Indeed, the conditions facing tech entrepreneurs in conflict contexts, such as Palestine, differ greatly from those associated with stable environments (e.g. Silicon Valley).The futures of innovation in conflicted countries need to be catalysed, created, and nurtured using sociotechnical processes hinged towards the normative aims of sustainable economic and social empowerment.

This suggests the imperative for a more inclusive, democratic, and just imaginary of the futures of innovation in Palestine. This new imaginary should aim to build new capacities and capabilities so that everyone can fully participate in the innovation process in a manner that does not reinforce the struggles of the Palestinian society.

Empowering, enabling, and cultivating, plural voices, in particular the voices of marginalised actors in the polity is necessary. A critical understanding of the grounded opinions and experiences of Palestinian innovation actors themselves would help to explore how innovation can be better used to aid the social and economic inequities that Palestinians face under the Israeli occupation. Additionally, inclusive partnerships that seek to respect and understand could facilitate increased sensitivity to social and economic implications of locally grounded needs, and in that sense contribute to a more ‘socially robust’ process of envisaging and navigating desirable innovation futures.

In tandem, encouraging institutional self-reflexivity with regards to assumptions and commitments, as well as more open communication about alternative, bottom-up imaginaries in informing the overall decision-making process, can open up opportunities for potentially increasing democratic legitimacy. Finally, the organisational conditions and co-dependencies of innovation practices, such as that between Israeli companies and Palestinian tech workers, must be considered in the building of a sustainable innovation future, especially within the circumstances of the occupation, as they ultimately will justify the types of investments in technological innovation, and carve out certain pathways for Palestine’s innovation ecosystem for years to come.

Bibliography

About. (2022). Asaltech.Com. https://www.asaltech.com/#about

About Us. (2022). Buildpalestine.Com. https://buildpalestine.com/about-us/

Abunimah, A. (2012). Boycott committee: Palestinian ‘Rawabi’ tycoon Bashar Masri ‘must end all normalization activities with Israel’. The Electronic Intifada. https://electronicintifada.net/blogs/ali-abunimah/boycott-committee- palestinian-rawabi-tycoon-bashar-masri-must-end-all

Aldairany, S., & Quoquab, F. (2018). Systematic review: Entrepreneurship in con- flict and post conflict. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 10(2), 361–383.

Baidoun, S., Robert, L., Maisa, B., & Awashra, S. (n.d.). Prediction model of business success or failure for Palestinian small enterprises in the West Bank. Journal of Entre- Preneurship in Emerging Economies, 10(1), 60–80.

Bayati, A. (2009). Rawabi Home. Live, Work, and Grow in the first Palestinian planned city. Rawabi.ps. http://www.rawabi.ps/newsletter/summer09/RH_English.pdf

Bayati, A. (2015). Rawabi Home. Live, Work, and Grow in the first Palestinian planned city. Rawabi.ps. http://www.rawabi.ps/newsletter/2015_winter/download/en/full.pdf

Bjørn, P., & Boulus-Rødje, N. (2018). Infrastructural Inaccessibility. CM Trans- Actions on Computer-Human Interaction, 25(5), 1–31.

Bjørn, P., & Boulus-Rødje, N. (2021). Tech Public of Erosion: The Formation and Transformation of the Palestinian Tech Entrepreneurial Public. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 31(2), 29–339.

Bjørn, P., Boulus-Rødje, N., & Ghazawneh, A. (2015). “It’s about business not poli- tics”: Software development between Palestinians and Israelis. ECSCW’15. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Oslo, Norway.

Burton, G. (2016). Assessing Palestinian Economic Exchange across the Green Line. Middle East Critique, 25(1), 45–62.

Fraiberg, S. (2010). Composition 2.0: Toward a multilingual and multimodal framework. College Composition and Communication, 62(1), 100–126.

Fraiberg, S. (2020). Unsettling Start-Up Ecosystems: Geographies, Mobilities, and Transnational Literacies in the Palestinian Start-Up Ecosystem. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 35(2), 219–253.

Global startup ecosystem report 2017. (2017). Startup Genome. https://startupgenome.com/gser2019

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford University Press.

Hidalgo, C. A. (2007). The Product Space Conditions the Development of Nations. Science, 317(5837), 482–487.

Hi-tech expert, Arees Bishara: The Silicon Valley project in Jerusalem is aimed at weakening the economic, social and political status of Jerusalemites. (2022). MIFTAH. http://www.miftah.org/Display.cfm?DocId=26760&CategoryId=34

Is Rawabi the extension of Silicon Wadi? (2019). Beit Magazine. https://beit-magazine.com/2019/12/15/is-rawabi-the-extension-of-silicon-wadi/

Jasanoff, S. (2015). Future imperfect: Science, technology, and the imaginations of modernity. In Dreamscapes of Modernity: Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power (pp. 1–33). Chicago University Press.

Kaufmann, Y. (2017). Start-Up Palestine: How to Spark a West Bank Tech Boom. Foreign Affairs, 96(4), 113–123.

Kozaczuk, D. (2015). The Hegemonic Ideal of Neoliberal Space of Peace. Rawabi, Palestine, a Case Study. Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies.

Lazareva, I. (2015). Meet the Palestinian Who Went From Throwing Stones at Israelis to Building a Town With Them. Time. https://time.com/4018306/rawabi-bashar-masri/

Lieber, D. (2018). With all his chips in, Palestinian businessman aims to build “Silicon Rawabi. The Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/ with-all-his-chips-in-palestinian-businessman-aims-to-build-silicon-rawabi/

Mann, M. (1999). The dark side of democracy: The modern tradition of ethnic cleansing and political cleansing. New Left Review, 235, 18–46.

Massey, D. (2005). For space. Sage.

Melhem, A. (2014). Rawabi still controversial among Palestinians. Al-Monitor. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2014/09/rawabi-city-west-bank-accusation-partnership-is rael.html

Mulas, V., Qian, K., Garza, J, & Henry, S. (2018). Tech start-up ecosystem in West Bank and Gaza: Findings and recommendations. The World Bank.

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/715581526049753145/Tech-start-up-ecosystem-in-West- Bank-and-Gaza-findings-and-recommendations

Palestinian BDS National Committee. (2012). Palestinian civil society denounces Bashar Masri’s normalization with Israel as undermining the struggle for Palestinian rights. BDS Movement. https://bdsmovement.net/news/palestinian-civil-society-denounces-bashar-masri%E2%80%9 9s-normalization-israel-undermining-struggle

Population. (2019). Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/site/lang__en/881/default.aspx#Population

Press, V. S. (2018). Hire The Neighbors: Could Israeli-Palestinian Tech Initiatives Prove To Be A Win-Win Arrangement? NoCamels. https://nocamels.com/2018/06/rawabi-tech-israeli-palestinian-initiatives/

Rosen, A. (2013). A Middle-Class Paradise in Palestine? The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/02/a- middle-class-paradise-in-palestine/273004/

Rubin, E. (2018). Make High-tech, Not War: Israel and Palestinians Forge Cutting-edge Coexistence. Haaretz.Com.

https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/business/2018-06-11/ty-article-magazine/.premium/mak e-high-tech-not-war-israel-palestinians-forge-coexistence/0000017f-e48a-d9aa-afff-fdda991b 0000

There are eleven universities in the region—But no jobs. (2019). Sueddeutsche.De. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/rawabi-silicon-valley-westjordanland-1.4303004-3

World Bank. (2019). Palestinian Territories. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/394981554825501 362/mpo-pse.pdf. Accessed 20 April 2020.